Polyvagal Theory 101

Polyvagal Theory (originally outlined by Dr. Stephen Porges and studied by Deb Dana) provides a map of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), defining how this system shapes experiences of safety and impacts our ability for connection. The stories you tell about yourself about who you are and how the world works begin in the ANS.

We come into the world wired to connect. Our ANS is built to help us feel safe in our bodies and in our relationships with others. Our ANS is always on guard, below the level of our conscious awareness, for cues of safety and cues of danger in our environment (a concept known as "neuroception").

"Because we humans are meaning-making beings, what begins as the wordless experiencing of neuroception drives the creation of a story that shapes our daily living." - Deb Dana

When our ANS detects danger in our environment, it has very skillful ways of protecting us from harm, keeping us alive, and allowing us to maintain connections with the beings around us. All of this protection happens in our nervous system and in our bodies, below the level of conscious awareness.

Your Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is made up of two main branches:

Parasympathetic

Sympathetic

And it responds to signals and sensations through 3 main pathways, or branches, each with a characteristic pattern of response:

Sympathetic

Ventral Vagal

Dorsal Vagal

The Autonomic Nervous System, flow chart

The sympathetic branch is found in the middle of the spinal cord. It is the pathway that prepares us for action. When it detects cues of danger in our environment, it releases adrenaline and ignites our fight or flight response.

The Sympathetic branch of the Autonomic Nervous System

In the parasympathetic branch, the remaining two pathways are found in a bundle of nerves called the vagus. The vagus travels in two directions: down through the lungs, heart, and diaphragm, and up to connect with nerves in the neck, throat, eyes, and ears.

The two pathways in the vagus nerve are the ventral pathway and dorsal pathway.

The ventral pathway repsonds to cues of safety and supports feelings of safety and connection.

The dorsal pathway responds to cues of extreme danger or life threat and takes us out of connection and into a protective state of collapse.

The Parasympathetic Branch of the Autonomic Nervous System: Ventral Vagal & Dorsal Vagal

Over time, our nervous systems evolved into the complex systems they are today, beginning with the dorsal vagal pathway, which developed first, followed by the sympathetic pathway, and finally the newest part of our nervous system: the ventral vagal pathway.

The evolutionary development of our Autonomic Nervous System

When we are firmly grounded in our ventral vagal pathway, we feel

safe

connected

calm

social

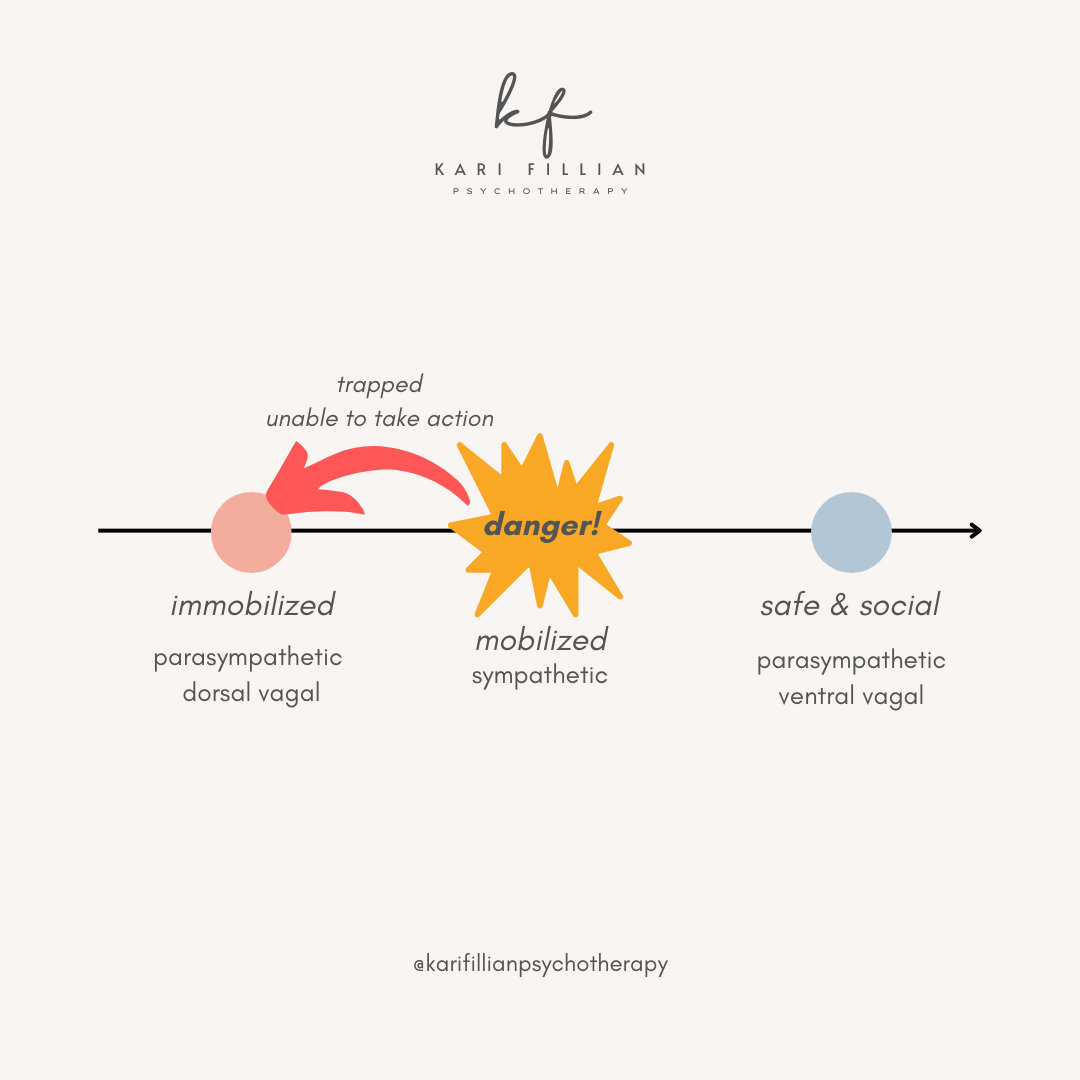

When we sense danger (even if its below our level of conscious awareness), we may be triggered out of our state of safety (ventral) and backwards evolutionarily into the sympathetic pathway, where we are mobilized to respond and take action. Taking action may help us return to a sense of safety.

However, if we feel trapped or unable to take action, our nervous system may activate the dorsal vagal pathway, leading to a state of collapse and shut-down, back even further in our evolutionary development. In this state we are immobilized in order to survive (think of the frog who plays dead in order to prevent the predator from attacking).

You can think of your nervous system like a ladder that you're always moving up and down. Your experiences change as you move up and down the ladder.

The Autonomic Nervous System Ladder

At the top of the ladder is the ventral vagal pathway.

When we are grounded in the ventral vagal pathway, we may experience:

Safety & connection

Heart rate is regulated

Breath is full and steady

Tune into conversations & tune out distractions

See the "big picture" and connect to the world

Experience the world as safe, fun, and peaceful

Able to take care of yourself

Able to engage in play

Feel regulated

Regulated blood pressure

Healthy immune system

Good digestion

Quality sleep

Overall sense of well-being

Moving down the ladder is the sympathetic pathway.

When we are triggered into this state, we may:

Feel a sense of unease & danger

Fight or flight response

Heart rate speeds up

Breath is shallow

Hyper-vigilance about danger in our environment

High blood pressure

Tightness &tension

Anxious

Angry

Rush of adrenaline

The world may feel dangerous, chaotic, or unfriendly

Difficulty focusing

Panic attacks

Relationship distress

The bottom of the ladder is the dorsal vagal pathway.

We drop into this state when all else has failed and we are unable to take action. We may experience:

Shut-down

Collapse

Dissociation

Hopeless

Feel a sense of aloneness

May feel abandoned

Foggy

Too tired to act or think

The world may feel empty, dead, and dark

Problems with memory

Depression

Lack of energy

Chronic fatigue

Low blood pressure

Your nervous system is a system that is brilliantly engineered to keep you safe and connected, and understanding how it works is the first step to healing if you are feeling stuck in the sympathetic or parasympathetic state.

If you are interested to learn more about how to use all of this information to create change in your life and heal your nervous system, please reach out to myself or another therapist who is trained in Polyvagal Theory. There are also a variety of resources that can support you on your healing journey, including The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation by Deb Dana, which was used to inform much of the information in this article. Other useful works by Deb Dana include her most recent book Anchored, as well as her website. I am incredibly grateful to her and Dr. Porges for bringing the work of Polyvagal Theory into my own life.